Iconology of the Devil Cards

From the Iconology Section of the Robert O'Neill Library

Introduction

The reader may be surprised to find the Devil numbered 14. But this is the number that has probably the best argument for being the original. The various orderings of the 15/16th century cards are discussed in some detail by Dummett (1980). Dummett's order Type B, which is followed here, has the best justification based on 15/16th century documents and is most likely the order followed in Ferrara, where we find the earliest mention of Tarot in 1442. In addition to having the best claim on the original numbering of the trumps, this ordering also seems to produce the closest fit to the iconology. We noticed, for example, that a number of the images of Death also showed the Devil, based on Revelations 6:8.

The reader will also notice that the themes of the "Triumphs" and the "Dance of Death" will not be considered in this chapter. The imagery associated with the Dance of Death - with each human condition linked to a dancing image of death appears to end with card 13. The tradition of the Dance of Death has no imagery that corresponds to the remaining cards. The imagery associated with Petrarch's "I Trionfi" will reappear in later cards, but the Devil is not described or even mentioned in the poem. The closest thing to an illustration related to the Triumphs is a 1496 woodcut that shows the defeated Cupid tied to a tree, death emerging from a coffin to the left, and a Devil on the right (Panofsky 1939, fig. 39).

The early images

Figure 1 shows the extant 15/16th century Devil cards. There are only 4 examples because none of the hand-painted decks contain a Devil. This may be simply because every one of the Devil cards has been accidentally lost. But the lack of a hand-painted Devil card may also indicated that the hand-painted decks are commissioned from earlier woodblock printed decks and the Devil was considered to be too dire a symbol and inappropriate for the noble patrons. But that is a matter for another essay.

Figure 1 shows the extant 15/16th century Devil cards. There are only 4 examples because none of the hand-painted decks contain a Devil. This may be simply because every one of the Devil cards has been accidentally lost. But the lack of a hand-painted Devil card may also indicated that the hand-painted decks are commissioned from earlier woodblock printed decks and the Devil was considered to be too dire a symbol and inappropriate for the noble patrons. But that is a matter for another essay.

The four surviving woodcuts show the Devil in a variety of different but related images. Three of the cards show the Devil with a trident. Two show bat-like wings. Three depict the devil with eagle talons and two show a second face at the abdomen or genitals. Two of the Devils are covered in hair/fur and three have beards. All have large ears and horns which are either bovine or goat-like. Two of the images show humans being speared or eaten. All of the Devils are depicted as standing. The task before us is to discover all of these details in representations of the Devil in the artistic milieu of Italy where the cards were designed.

The Devil in religious art

The Devil appears in Christian art from at least the sixth century. Menghi (2002) gives an excellent review of the theology of the Devil from early Christianity and its Pagan roots. But the early examples such as the mosaic at S. Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna ~500 (Link 1995, p 110) and illustrations in a manuscript of 970/80 (Link 1995, p. 86) simply show a dark angel with bird wings and halo (Russell 1984). Early monumental art (12th century) shows the devil with a huge head, flames for hair, and animal paws (Link 1995, pp. 21 and 49) or birds wings (Ibid. pp. 64 and 91).

It is not until the latter half of the 12th century that the Devil begins to look familiar. Book illustrations show a hairy beast with curved horns (Voelkle and L'Engle 1998 p. 28, Link 1995 p. 51) but with birds' wings, human feet and a second pair of wings at the buttocks. A painted altarpiece of the 13th century shows the Devil with horns and bovine head but no wings, wearing a skirt, and with animal paws (Link 1995 p. 100).

Only in the 14/15th centuries does the familiar symbolism appear. A 1477 engraving (Andre 1996 plate 48) shows the Devil with bat wings and eating a person (Fig. 2). An illuminated initial (Voelkle and L'Engle 1998 p. 262) ~1470 shows the eagle talons and a face at the genitals. An illustration from ~1405/10 (Ibid., p. 266) shows bat wings, curved horns, and the devil is eating people and carrying them on its back. Figure 3 shows an example from an Illustrated Prayerbook of Rouen (~1495). In this case, the devil has a face at the abdomen/genitals, curved horns and large ears.

Only in the 14/15th centuries does the familiar symbolism appear. A 1477 engraving (Andre 1996 plate 48) shows the Devil with bat wings and eating a person (Fig. 2). An illuminated initial (Voelkle and L'Engle 1998 p. 262) ~1470 shows the eagle talons and a face at the genitals. An illustration from ~1405/10 (Ibid., p. 266) shows bat wings, curved horns, and the devil is eating people and carrying them on its back. Figure 3 shows an example from an Illustrated Prayerbook of Rouen (~1495). In this case, the devil has a face at the abdomen/genitals, curved horns and large ears.

Figure 4, from the Visconti psalter (1402-1425), illustrates the final plague that God brought upon the Egyptians (Exodus 12:21-30). The image of the devil is shown as hairy and bearded, with curved horns, large ears, with eagle talons and bat wings. But at this early point in the 15th century, the Devil still doesn't have the three pointed trident found on the Tarot images (Fig. 1).

Once the familiar details of bat wings, eagle talons, etc. appear in the 15th century, they are rapidly adopted. The details appear in illustrated psalters of 1415 and ~1425 (Link 1995 pp. 102 and 142) and a manuscript of 1409 (Link 1995 p. 178). A similar image also appears in the chapel of San Petronio, Bologna in a 1411 image of hell (Welch p. 265).

Menghi (2002) provides a sixteenth century exorcism ritual in which an image of the devil painted on paper is burned as an integral part of driving the devil from the possessed person. Surely a strange example of orthodox image magic pointing to a belief in the efficacy of manipulating a physical image.

The apocalyptic tradition

The imagery of the Devil in the Apocalyptic literature parallels the development of the symbol in other religious art. Revelations describes the Devil as "the beast that comes out of the Abyss..." (11:7) and "The great dragon, the primordial serpent, known as the devil or Satan..." (12:9). The most specific image is given in 13:1/3: "Then I saw a beast emerge from the sea: it had seven heads and ten horns, with a coronet on each ot its ten horns...the beast was like a leopard, with paws like a bear and a mouth like a lion..."

The early illustrations of Revelations follow the written descriptions and depict the Devil as a seven-headed dragon. It isn't until the 12th century that we begin to see images of the hairy, bearded Devil with eagle talons (Emmerson and McGinn 1992, fig. 14). Examples continue into the 13th century (Fig 5) but it not until the 14th and 15thcenturies that the details in the Tarot symbol become common. Figure 6 shows Giotto's version of the Devil from a 1306 fresco in the Arena chapel in Padua. Giotto used the curved horns and beard, eagle talons and has the devil eating (and defecating) humans. Notice that the artist has integrated elements from the description in Revelations by showing a serpent behind the Devil's head and two dragons on which the Devil appears to be sitting. Another example can be found in Fra Angelico painting ~1431 (Grubb 1997, p. 112).

The early illustrations of Revelations follow the written descriptions and depict the Devil as a seven-headed dragon. It isn't until the 12th century that we begin to see images of the hairy, bearded Devil with eagle talons (Emmerson and McGinn 1992, fig. 14). Examples continue into the 13th century (Fig 5) but it not until the 14th and 15thcenturies that the details in the Tarot symbol become common. Figure 6 shows Giotto's version of the Devil from a 1306 fresco in the Arena chapel in Padua. Giotto used the curved horns and beard, eagle talons and has the devil eating (and defecating) humans. Notice that the artist has integrated elements from the description in Revelations by showing a serpent behind the Devil's head and two dragons on which the Devil appears to be sitting. Another example can be found in Fra Angelico painting ~1431 (Grubb 1997, p. 112).

A number of artists worked on the Baptistery in Florence so we cannot be certain if Giotto is responsible for the mosaic devil in the cupola (Figure 7). However, this image also incorporates the serpent theme from Revelations, showing serpents emerging from the devil's ears. Other examples of the mixed symbolism is found in a 15th century psalter (Grubb 1997, p. 107) where the Devil is shown with serpent-like scaly skin and a psalter of ~1413 (Grubb 1997, p. 119) where the devil is furred but has a scaled abdomen. Figure 8 is taken from an Apocalypse of ~1400 and is an illustration of Revelations chapter 22. The devil in this image has many of the Tarot details including curved horns, beard, hairy body, wings, talons, and face at the abdomen. The number of matching details in these contemporary Apocalyptic images suggests their influence on the Tarot designers.

Figure 9 is from a 14th century Bolognese painting of the Last Judgment. The figure shows the devil with curved horns, hairy body and a face at the abdomen. Bat wings and talons can be seen on the devil to the upper right. Once again we find many of the details in the early Tarot card also appearing in the public art of the time.

Figure 9 is from a 14th century Bolognese painting of the Last Judgment. The figure shows the devil with curved horns, hairy body and a face at the abdomen. Bat wings and talons can be seen on the devil to the upper right. Once again we find many of the details in the early Tarot card also appearing in the public art of the time.

Iconological analysis

The imagery on the early Tarot cards (Fig. 1) appears to be explained by the religious art available in the early 15th century. The details in the Tarot Devil appear in depictions of hell and especially in illustrations of the Apocalypse. The one exception appears to be the trident that occurs on 3 of the Tarot cards.

Link (1995) provides a detailed analysis of the imagery used to represent the Devil between the 6th and the 16th centuries. According to his analysis, the trident derives from the trident of Poseidon, which, in turn, comes from the triple lightning of the Babylonian god Adad (Van Buren 1945). The trident appears in the earliest examples such as a ninth century psalter (Link 1995) but then essentially disappears until the second half of the 14th century. During the intervening period, the devil is shown with a two pronged grapnel (see fig. 4). The earliest example of the trident may be an apocalypse of ~1340 (Grubb 1997, front cover). However, the trident does not become a common feature of the Devil symbol until the 15th century (e.g., Morgan and Morgan 1996, p. 13). So the presence of the trident on the Tarot images certainly marks the Tarot Devil as the late 14th or 15th century.

As we found with the symbol of Death, the image of the Devil used on the early Tarot cards is not an ancient image. Early Christian art represented the Devil as an angel and the older apocalyptic tradition shows the Devil as a dragon or serpent. The Devil as a furry beast only appears in the late 12th century. Details such as the bat wings do not appear until the 14th century (Link 1995). Russell (1984) concludes that the Devil became more and more grotesque beginning in the 14th century. So the details on the early Devil cards really argue against theories that assign an earlier date to the origin of the Tarot.

As we found with the symbol of Death, the image of the Devil used on the early Tarot cards is not an ancient image. Early Christian art represented the Devil as an angel and the older apocalyptic tradition shows the Devil as a dragon or serpent. The Devil as a furry beast only appears in the late 12th century. Details such as the bat wings do not appear until the 14th century (Link 1995). Russell (1984) concludes that the Devil became more and more grotesque beginning in the 14th century. So the details on the early Devil cards really argue against theories that assign an earlier date to the origin of the Tarot.

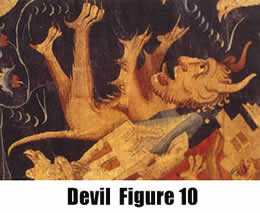

In the chapter on Death, we saw several images that combined Death with the Devil and even one that combined Death, Devil and Tower. Russell (1984) points out that the combined imagery of Death and the Devil doesn't begin until the 11th century. In fact, in one 9th century image (Russell 1988, p. 50), it is the Devil rather than Death that is leading off the living person. Figure 10 shows a tapestry ~1373/81 that depicts a devil along with towers falling. So once again we find that the symbols in the Tarot trumps appear in groups, at least within the Apocalyptic tradition, showing an association of Death, Devil and Tower that follows the sequence in the type B decks and documentation from the 15/16th centuries.

Interpretation

The 15th century card-player would probably have associated the Devil with the Death symbol as the ultimate fate of the sinner after death. Even though the horns and beard of the Devil are probably derived from the god Pan, the cult of Death in the 15th century would have argued against seeing the Devil as a playful forest spirit. The early Tarot images (fig. 1) don't depict playfulness as the Devil eats bodies and spears them with its trident! Furthermore, the early Tarot images are more bovine than goat-like as one would expect if the viewer was meant to see Pan.

The context in which the 15th century card-player would most likely have seen the Devil image would have been in representations of the Apocalyptic Last Judgment. The Franciscan preachers used the approaching end of the world and eternal damnation as a central theme of their homilies (Russell 1984). Therefore, the Devil might have elicited feelings of anxiety and the need for repentance.

But to the late medieval mind, the Devil was not just a passive evil that received sinners after death. The Devil was an active force in this world as well. The phenomenon of demonic possession was an accepted concept and learned theologians discussed possession. The Church included instructions on exorcism in the Rituale Romanum, the book of officially approved rituals (Menghi 2002)..

One aspect of belief in the Devil's influence relates to the sixth century legend of Theophilus (Russell 1988). Theophilus was a cleric who made a pact with the Devil to obtain ecclesiatical promotion. Though it sounds strange to our ears, it was a wide-spread and common legend that accounts for the almost universal belief in demonic pacts. One aspect of this belief was that worldly success was often suspected as being the product of a pact with the Devil. How else could one explain success in one who was not saintly and achieved success through violent or evil means? Either God is unjust, or the individual had the assistance of demonic forces through a pact. I suspect this is one of the reasons that the nobility never had the Devil card included in their Tarot decks. Its presence might have raised (or confirmed) suspicions about the reasons for their success.

Another consequence of the Theophilus legend was the widespread belief that heretics were involved in pacts with the Devil. In an age of faith, the truth of Christianity seemed obvious and indisputable. How else could one explain the errors in a heresy unless the heretic was under the direct influence of the Devil? This belief was reinforced by the experience with the dualist Cathari heresy. The radical dualists saw the Devil as a co-equal force, antithetical to God. Moderate dualism, more characteristic of the Cathari, saw the Devil as an active force conspiring to maintain evil matter and prevent release of the human spirit. Perhaps the nobility prudently excluded the Devil to allay suspicions of heresy? After all, Pope John XXII (1316-1334) had instructed the Inquisition to move aggressively against witches and sorcerers.

Finally, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the Devil image would have elicited thoughts of Black Magic. The belief in demonic magic was widespread (Kieckhefer 1989) in Europe. Several manuals for summoning demons have survived (Kiechhefer 1997, Fanger 1998) and the belief in the effectiveness of demonic ritual was essentially universal (Shumaker 1972) and the second half of the 15th century witnessed the atrocity of witch-burning.

Russell (1988) provides an insightful analysis of the factors that led up to the belief in witches and demonic magic. First, scholastic theologians had concluded that magic was necessarily demonic. Second, European folk mythology was full of tales of vampires and demons. Third, medieval Catharism and its aftermaths focused attention on the power and influence of the Devil. Finally, a strange perversion of the concept of judicial precedent became established. Confessions of demonic ritual, under threat of torture, were accumulated as evidence for the validity of the phenomenon. So perhaps we should not be surprised to find that the aristocratic patrons omitted the Devil from their hand-painted decks.