Fool Cards

The Iconology from 15/16th Century

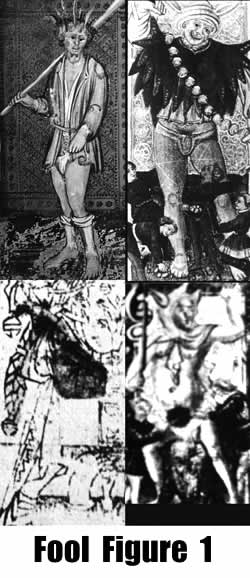

Figure 1 shows the four intact cards from the 15/16th century decks. The fool appears in a variety of guises from the goitered idiot with feathers in his hair to the homeless man with bells to warn of his approach. In two cases, he is being played with or tormented by children. In all cases he is carrying an object: a staff, a branch, or a belt of bells. In two cases he has a foolscap with the ears of a jackass. In all cases his clothing is inadequate.

There is a fifth image, a sliver of a card in the Cary-Yale woodcut sheet (Kaplan 1986, Volume II, p. 286), this shows a man walking to the viewer's right with a staff and perhaps a pack on his back or perhaps it is a hat with chinstrap that has been thrown back. He appears less disheveled than the fools in Fig. 1 with a cloak and boots and looks like a medieval image of a pilgrim, e.g., Walker (1984, fig. 26). The sliver of a card is shown in Figure 2. I have chosen to show this example separately because of an interesting relationship with the Bagatto card that appears to its left. Notice that the three-tiered pack (or hat) on the Fool's back appears to be the same, or similar, to the three-tiered pack (or hat) on the Bagatto's back. A relationship is also suggested in another woodcut (1). We will return to the interesting relationship between these two cards later in the chapter.

Images of the Fool were common in Medieval and Renaissance artistic traditions. Secular sources, such as Brant's "Narrenschiff" (Basle, 1494) show the fool with foolscap, crutch or staff, barefoot and with leggings falling. Images from this source are discussed by Hind (1935) and an example can be seen here (2).

A fool image also appears in the "Tarocchi of Mantegna" as Misero (3). Another secular image appears in a ~1403 treatise on astrology (Figure 3). Here the Fool appears as a disheveled lunatic, pointing up to the moon and under its dominion.

Religious tradition

The Fool commonly appears in general religious art. Giotto illustrated one in the fresco of Foolishness, one of the seven vices illustrated in the Arena Chapel in Padua (1306) (4). The Fool appears barelegged, with feathers in his hair and a staff/club that resembles one of the early cards (Fig. 1).

A typical Fool image appears as beggar in a 13th century illustrated life of John the Baptist (Figure 4). The image shows the foolscap, cane, and bare feet. Interestingly, this version shows, not a pack, but a child being carried on the Fool's back.

The Fool often appears in illustrated Psalters because of Psalms 13 and 52: "The Fool says in his heart: 'there is no god'". Figure 5 appears in an early 15th century psalter as an illustration of Psalm 52. The Fool wears an animal skin and carries a stick under his arm. A similar illustration showing the Fool dancing while the king prays can be found in Davidson (1989, Fig. 4). Other examples from 14th century psalters can be seen at (5), (6), (7), (8), and (9).

Triumphal tradition

The Fool does not appear in Petrarch's poem and is rare in the Triumphal tradition. The only example I am aware of appears in the middle tier of images at the PalazzoSchifanois in Ferrara, under the Triumph of Minerva (1476-1484) (10).

Moakley (1966) identified the Fool as a character in her Petrarchian festival. But the imagery does not appear. The only real possibility is that the Fool represented Petrarch himself - the non-participant in the procession, that is occasionally illustrated on a hillside in the background observing and learning. But this identification seems forced and really isn't justified by the imagery in the early Tarot cards.

Dance of Death tradition

The Fool seldom occurs in the artistic tradition associated with the Dance of Death. The only examples that I am aware of can be seen at (11) and (12). The rarity is likely due to the enigmatic position of the Fool in the Moral Theology of the Middle Ages. The Dance of Death represents the allegory of various estates of persons, forced to face the moral consequences of their actions. But to commit a serious moral evil, a person must be fully conscious and aware of their action. Fools and madmen are like children and were not morally responsible. Their exemption from punishment after death appears as early as 12th century tracts (Gurevich 1988) and was confirmed by the Scholastic theologians such as Thomas Aquinas (Davidson 1996). The Fool was outside the normal 'estates' and could face death with impunity.

Apocalyptic tradition

The Fool does not appear as a character in Revelations and the image of the Fool does not appear in the artistic tradition based on Revelations.

Iconological analysis

The Fool would have been a familiar and recognizable character in the city-states of northern Italy where the Tarot was designed. Living on charity and exempt from the moral and civic obligations of other citizens, the Fool moved freely through late Medieval urban society. Husken (1996) points out that as a street-person the Fool participated in religious, royal, and theatrical processions just as postulated by Moakley (1966).

The Fool frequently appears as a character in late Medieval and Renaissance dramas. These plays provide a unique opportunity to analyze how the Fool was viewed within the society that produced the Tarot. In 15th century morality plays, the Fool appears as a character called "Nought" who is subject to derision because he plays no attention to morality (Davidson 1989). In an early poem, "A Tale of Three Score Fools" the Fools are under the patronage of Bishop Nullatensis (Davidson 1989). In both these cases, the association of the Fool with zero is clear.

But the Fool also appears as a far more complex character. In some instances, he falls in with a trickster (Leslie 1996), an association that was pointed out earlier in connection with Fig. 2. The distinction is made between the 'natural' Fool who is ignorant and mentally disturbed and the 'artificial' fool who is actually perfectly sane, a sly trickster who pretends to be a fool (Happe 1996). This association may help explain the juxtaposition of the Fool and Bagatto cards in the Tarot deck. This was an association that the card-player is likely to have seen before.

In the medieval morality play, the Fool who lacks discipline and morality is seen as an evil example and temptation for the society around him. In a few illustrations ( see Davidson 1989, Fig. 3), the Fool is depicted as the Devil. In turn, the character Titivillus is actually the Devil but becomes a silly and comic character that causes little harm (Gifford 1974). This enigmatic Fool/Devil association does not appear to have carried over into the Tarot.

In a 16th century morality play, the main characters find three ladders which symbolize the three estates : church, nobility, laboring classes - each ladder has 7 rungs. This shows an interesting parallel to the structure of the 21 Trumps, but probably simply reflects the importance of the numbers 3 and 7 in the numerology of the times. More interestingly, the church ladder has prudence as its first rung. However, the character in play says it is actually folly (Husken 1996). Perhaps this is another hypothesis to explain the missing virtue of Prudence in the Tarot?

There is a second body of literature which does not bear directly on the Renaissance image of the Fool, but on the combined Fool/Magician as an archetypic image. Radin (1972) points out that the "trickster" appears as a character in ancient Greece, in Chinese and Japanese stories and in the Semitic world as well. Most of the 300 native American tribes, belonging to 7 different language families, have trickster tales. Pelston (1980) discusses the trickster archetype in West African stories. The universality of the trickster, across cultures, was the primary criterion used by Jung to argue for the archetypic nature of an image. Jung argued that such images were produced by the unconscious rather than being transmitted through cultural means (Jung 1954).

Lindquist (1991) examines the Winnebago legends and develops the theme that the trickster is 'everyman'. A life symbol embodying the foolishness, spontaneous wisdom, and human errors of everyone. However, the trickster remains very much a religious figure. The tales are moral lessons on the pitfalls of maturation.

What becomes clear from the study of medieval drama and the archetypic myths of the trickster is that the Fool/Magician is, like all archetypic images, enigmatic. The Fool is lacking in clear rational thought, but can surprise the wisest with spontaneous wisdom. One is reminded of a modern Fool, Yogi Berra, who said that if you don't care where you are going, "You ain't lost". The Fool is devilish in the tricks it plays, but innocent of any moral consequence of the tricks. This enigmatic character is typical of archetypic images. For example, the simple figure "O" can mean both zero/nothingness and also can be a symbol for completion. The essential question is asked by Willeford (1969, p. XV):

"Why is the fool, as bumpkin, merrymaker, trickster, scourge, and scapegoat, such an often recurring figure in the world and in our imaginative representations of it? Why do fools from widely diverse times and places reveal such striking similarities? Why are we, like people in many other times and places, fascinated by fools?"

Interpretation

When we take the archetypic image of the Fool into the environment of the 15th century card-player, several additional aspects of the image should be emphasized (Swain 1932). Walsh (1996) points out that the Fool, even the Fool supported by the ducal court, was not an honored guest. He was given only table scraps to eat, often beaten, ridiculed and subjected to the playful harassment shown on some of the early Tarot cards (Fig. 1).

The possibility that the fool could do evil through ignorance was never forgotten. But in literature and drama there is also a recognition that the Fool is also a model for the holy (Happe 1996). The Fool was never given the glowingly positive qualities attributed to the Tarot Fool in the modern period (Davidson 1996). But there was always the reminder that the devout would also appear as fools because of their rejection of society's rules (Saward 1980).

Hern-Allen (1979) points out that "Fool" is a term used for the spiritual aspirant in many religious paradigms including Islam and Zen Buddhism. The term was used for some of the early Christian desert Fathers (Krueger 1996). The card-player may not have been aware of these references, but was well aware of 1 Corinthians 4:10 ("we are fools for Christ's sake") and would have heard the revered Saint Francis of Assisi referred to as a fool (Green 1983). So although the homeless Fool of the streets would likely have been the first impression to strike the mind of the ordinary card-player, it is also reasonable to assume that the religious image was sufficiently familiar to have arisen as well.

The Fool's journey

Modern interpretations of the Fool card often interpret this card as the initiate setting out on a quest for self-development, the Fool's Journey. So the question arises as to whether this concept could have been in the minds of the 15th century designers. The answer, surprisingly, is that the proposal is quite feasible!

The concept of the religious pilgrimage was, of course, a familiar one: "strait is the gate and narrow is the path which leadeth to life and few there are that find it." (Matthew 7:14). The card-player probably knew someone who had journeyed to a shrine or repository of a miraculous (i.e., magical) relic or icon. The venacular epics of Dante and Petrarch were well-known examples of the ignorant poet being exposed to a sequential hierarchy of experiences that led to wisdom. Dozens of the 14th-17th century epic/chivalrous poems feature a journey/pilgrimage into hell (Turner 1993). Apocalyptic themes were assimilated into the grail quest literature by the 14th century (Emmerson 2000). In addition, the image in Figure 2 looks more like a pilgrim than the typical Fool.

Even if the card-players had limited access to the courtly poets, they were certainly familiar with the dozens of folk legends of otherworldly journeys (Haas 2000). It is beyond the scope of the present study to review these stories in detail and the interested reader is referred to Gurevich (1988) and Gardiner (1989). These traditional stories range from moral allegory to thinly veiled mystical journeys. And we must agree that at least one of the 15/16th century cards (Fig. 2) show the Fool as a journeyer.

The evidence is not strong enough to demonstrate that the theme of the Fool's Journey played an important role in the design of the cards. However, the theme was a part of the culture in which the cards were designed. Therefore, we cannot dismiss offhandedly the suggestion that a hierarchical pilgrimage or quest played some role in the design and early interpretation of the cards.